To reach a sound quality of sufficient richness and roundness, the dedicated artisan takes over two months, using skills so steeped in tradition they have changed little in the last two centuries. Even in today’s information age, modern technology is largely absent from the workshops of guitar makers, who can make two identical guitars that end up sounding different. No one knows why – it’s just the magic of ‘El duende’.

The top guitar makers (luthiers) of today are masters of selecting materials and design features in order to create precise sound performance. They interpret the subjective desires of customers and use their accumulated knowledge to construct beautiful instruments that deliver the sound balance they want. But the very fact that luthiers follow painstaking, traditional construction techniques moves many to believe that the evolution of acoustic instruments has essentially reached its limit.

Strange bedfellows

But technology might just hold the answer according to a group at Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya – BarcelonaTech. Here, a diverse collection of engineers, acousticians, material scientists, and museum curators have come together with one of Spain’s top luthiers in an attempt to deepen the understanding of what makes guitars sound like they do. They are analysing the vibrational and acoustic performance of concert-grade classical guitar components throughout the construction process, beginning with just the soundboards, and steadily working up through different stages of completion to the final, finished guitar. Then, in a second phase, they are analysing antique guitars from long-dead masters like Antonio de Torres, with the kind help of the Museu de la Música de Barcelona. Since obviously the group cannot unglue these components of Spain’s heritage, the group instead characterises the complete instrument, and then draws revealing comparisons with the results gleaned from modern instruments.

Ultimately, they hope to find relationships between the structural properties and the acoustic performance of the very best guitars, to help understand how to select materials and construction methods better than ever before.

“It’s an ambitious project,” admits Marco, the acoustic expert and keen guitar player leading the effort. “Working with historical instruments in my country is pioneering, and research into guitars has not been done with an interdisciplinary group like this before.” It took considerable effort to bring together: engineers were not used to working with musical instruments, while luthiers were initially sceptical, fearing the engineers’ mathematical ways entering their artistic domain.

The artistic domain

Antonio Manjón makes some of the top guitars in the world today. He met Marco at a conference and became intrigued by this opportunity to develop his understanding of guitars. For Antonio, it was a new way to gain some deeper insights into different woods, constructions, and how they interact while, for Marco, it was a perfect catch: now he could test throughout the development process of a master.

“I think knowledge based on experience and tradition is also a type of scientific knowledge, just done by instinct. The luthier intuitively analyses and creates solutions based on that analysis, and even though the process is in many cases unconscious, it is still an analytical process,” says Antonio. “Among us guitar makers there is some mistrust of science; it has rarely been seen as another tool that we can use, and we need to break this wall. I want to feed this intuition with new knowledge that will make this intuition take more accurate decisions each time, and I think science can contribute to it.”

Convincing the museum

For Marco meanwhile, having won top prize in the luthier search, he still had a lot of convincing to do at the museum, where it turned out that asking to ‘hammer test’ irreplaceable antiques doesn’t go down very well. “It sounded a bit brutal,” says Antonio. “So we decided it would be better to call it ‘impulse’ testing.” Finally, Marco’s demonstration on his own concert-grade guitar – with a polyamide protector between the hammer and guitar – convinced the museum to allow modal testing on the cherished classics.

Building on a wooden tradition

What makes a guitar sound good is about 50% down to the quality of the wood, and 50% the skill of the luthier, according to Antonio. But the wood selection itself is part of the luthier’s skill. As Marco explains, “The traditional process of material selection is dictated by a set of requirements which include not only the type of wood, the orientation of the cut and the general width of the annular rings, but also a certain raw acoustic characteristic which is empirically determined by tapping the plank and listening to its response.”

Small details make all the difference. “It is relatively easy to get a good guitar, if you work with quality material,” says Antionio. “Making an outstanding guitar is much more difficult.” To do this, it is vitally important to anticipate cumulative and synergistic consequences in as much detail as possible. “There are many choices to make, and it would be very helpful to know more and be able to quantify the sound I will obtain if I do certain things like changing rib positions,” says Antonio.

The new norm

Nowadays, customers want a precise balance of sound characteristics, but communication about guitar sound uses concepts and words that are difficult to quantify and explain, like ‘sweet’, ‘clear’, ‘rich’, ‘deep’, and ‘round’. “If you only support this with your intuition, then the message might not be that concrete,” explains Antonio. Players’ needs and tastes for guitar sound have also changed. Guitars are now conceived of as instruments for chamber music or individual playing, so luthiers look to increase sound power – requiring new construction methods.

Their traditional selection process is complicated by the fact that compared to the days of masters like Antonio de Torres, access to quality woods is democratised and people can easily access more exotic wood like Canadian Cedar, Mexican Rosewood, Ziricote, etc. There is now more information available about it too, but, Antonio says, that does not equate to knowledge. “I think we have lost knowledge because in many cases it is not necessary,” he says. “Society is much more specialised today and this makes the knowledge more parcelled. However, ancient knowledge was much more global; the luthier needed to know the whole process of wood in terms of growth, cutting, drying, and transportation.”

LAN-XI DAQ

Science serves intuition

Given all these challenges, the project aims to overcome the ‘stalled’ design evolution by adding more knowledge, in order to understand guitar construction more intricately than ever before. By rapidly building a knowledge base, they plan to help anticipate the interactions of different woods and construction methods. Importantly, they use scientific means to foster – but not replace – the intuitive tradition of the luthier.

Analysing the resonances of guitars

The loudness and richness of the instrument depend considerably on the behaviour of the soundboard’s resonant frequencies. Consequently, the project follows five soundboards made from German Spruce through their production, throughout their incorporation, and finally in the finished guitars. It takes about a year to make five guitars, but so far the structural properties in terms of the modal parameters have been obtained for each stage, from the initial flat shape up to the finished soundboard.

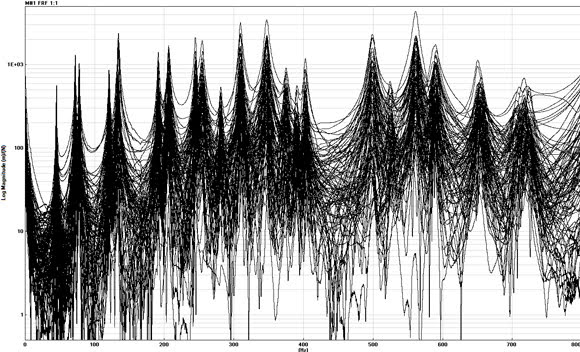

Soundboard frequency response

Each curve represents a hammer strike, giving a Frequency Response Function (FRF) for the soundboard. Usually, a large number of peaks is desirable since each represents a natural resonant frequency that amplifies the input – creating a richer sound. The width of each peak is also critical, since it is related to the structural damping and therefore to the sound energy dissipation. In general, the lower the damping the better it is for a guitar’s sound. Luthiers are naturally adept at ensuring this without the aid of frequency spectra.

The effect of tuning

They have also investigated the effect of tuning. “I like guitars that differentiate the different voices of the strings, so that you can hear each string clearly,” says Antonio. “Varying string tension can make the peak amplitudes of the string coincide with the peaks of the frequency spectrum of the soundboard,” says Marco. “The result is an unbalanced instrument.” Complicating matters, some older guitars are no longer able to reach the normal tuning pitch.

Lessons for the master?

So what is it like for a master craftsman to see his inherent talents displayed on a graph? “On one side, it’s a bit cold because you cannot see the love and passion that has gone into it on a graph,” says Antonio. “But on the other hand, it’s surprising that you can get so much information from just one hammer strike. And we have made 12,000 strikes during the study. The biggest learning from this is discovering all the possibilities there are, and seeing how deeply you can understand sound.”

Surprises for Antonio included the symmetry of the soundboard. “I thought that the structure being symmetrical would impart the sound equally between the high and the low tones, but an asymmetric design made the high notes more stable,” says Antonio.

For Marco meanwhile, the most significant parameter obtained so far is the equivalent stiffness of the soundboard. “When luthiers manufacture a soundboard, they apply a bending load with their thumbs to evaluate the stiffness of the plate. In fact, what they are doing is determining the transverse equivalent stiffness of the soundboard. According to their knowledge, they reduce the thickness of the plate or the distribution of the supporting ribs in order to achieve a desired stiffness. We have quantified this inherently qualitative parameter. During the initial process, the different soundboards presented different transverse stiffness. At the end of the process, the stiffness values converged. It proves that the luthier is able to estimate this property and work to achieve a desired behaviour.”

They have also confirmed some things that Antonio already knew, finding that a thicker ‘fan’ of supporting ribs increased the stability of the instrument. “The response from the instrument is much clearer when the fan work is more advanced, with more resonance and longer sound duration, so the frequencies are more stable throughout,” he says. In addition, they have quantified the effects of the wood’s moisture content upon the structural properties and the vibration response.

Progress so far

“It’s a fascinating subject and a promising research area with so much still to do, like studying the effect of different couplings between the backboard and the soundboard,” says Marco. But to advance, more funding is needed. One of the biggest challenges, and an important goal in itself, has already been achieved: the creation of an interdisciplinary group around music and acoustic research, and the application of technology and equipment in fields that traditionally have been far removed from engineering.

“When one is working far from his own field, it is always an enriching experience,” says Marco. “But for me, the most interesting part has been to see how important the intuition is. To create a superior instrument it doesn’t matter what level of scientific knowledge you have. Intuition, scientific and critical thinking, however, are essential.”

So what of the mystery of El Duende? “In my opinion,” says Antonio, “El Duende appears as you work according to your knowledge together with commitment, love and passion. That’s the mystery.”

뉴스레터를 구독하고 소리와 진동에 대한 최신 이야기를 만나보세요