Why do you do what you do?

What makes acoustics especially interesting to me is that it combines both physics and psychology. The ultimate judgement as to whether an acoustic engineering project has worked is usually made by a human (for example, a member of the public) listening to the results. Understanding the human mind is one of the most exciting areas of research at the moment.

What initially drew you to acoustics?

I played music throughout my childhood, and combining my interests in music with my expertise in physics seemed the perfect combination for my PhD studies.

What are the challenges and rewards of your work?

In general, people in acoustics have to work hard to get sound to be given sufficient priority. Modern human beings are very focused on sight and this bias permeates academia and industry. I’m always fighting to ensure sound isn’t completely overlooked.

Teaching students is the most challenging and rewarding part of my job. There will always be students who struggle at some point during a course, and so it is a constant challenge to try to come up with new ways of putting across complex concepts to help their learning. However, it is very rewarding, and I particularly like hearing about what our graduates are doing. Salford has been running acoustics courses since the 1970s, so we have graduates across the world in many different industries. One of the nice things about social media, is nowadays you get to hear about what they’re doing.

Is there a turning point or defining moment in your work?

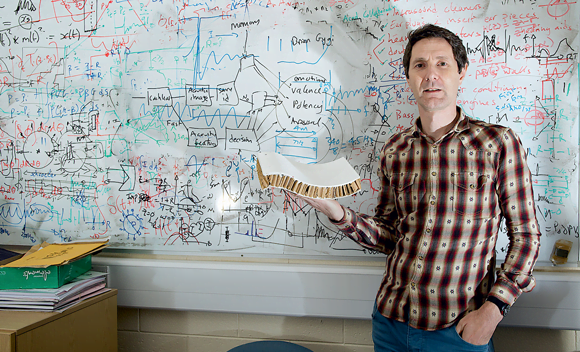

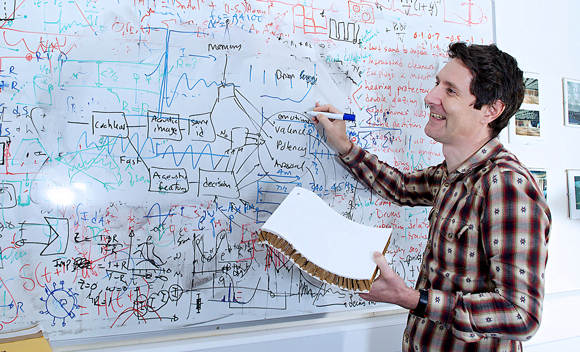

My first area of research was in the design of room acoustic diffusers for studios and performance spaces. I spent my PhD understanding how they worked. I then realized I could use numerical optimization to allow designs of any shape. This was a key development, because it enabled diffusers to match the visual requirements of architects, and has led to my designs being used worldwide. As an engineer, seeing your research being exploited is immensely satisfying.

You’re a professor of acoustics who regularly appears in print, onstage, online, on radio and television – from the New Scientist to The Royal Albert Hall to YouTube and the BBC. How do you reconcile the academic with the public persona?

If you meet me face-to-face you’ll find I’m a typical introverted engineer, a typical Englishman almost poleaxed by the fear of causing embarrassment, but one who is also very good at pretending to be outgoing! I’ve never tried to cultivate a public persona. Friends have commented that it is funny reading my popular science book 'Sonic Wonderland', because it feels like I’m having a conversation with them.

You seem very comfortable with social media – how has this changed the way you approach your work?

I see Twitter as a publicity game that I have to play. Although that sounds negative, there are some real positives, like when people tweet to say they’ve enjoyed a radio programme. It can also be a useful research tool for asking questions.

Any personal ambitions unattained?

It would be nice to present a TV documentary. But it’s hard to get a sound documentary on TV that isn’t about music, because commissioners always think audio is better suited to radio. Failing that, I’d like to get a returning programme commissioned on BBC radio. I’m making a pilot for such a series this spring.

Many acousticians have an incredible understanding of and true talent for music, many of them proficient in playing a number of musical instruments. Are acousticians frustrated musicians?

There’s a big difference between being a professional and amateur musician. Being an amateur you can concentrate on enjoying it – very different to being a professional. I think if I were a professional musician, the joy would go out of playing.

Your projects seem to range from serious to quirky – making music from vegetables, acoustic analysis of the world’s 'longest echo' and the science of scary screams to name but a few. What was your favorite project?

Hunting the sonic wonders of the world was very special because it took me around the globe to hear so many different sounds in so many strange places: a military oil tank in Scotland with the world’s 'longest echo', booming sand dunes in the Mojave Desert and an organ made out of cave formations to name just three examples.

Any unexpected outcomes to any of them?

I was pretty sure that the military oil tank in Scotland would break the world record, but I was surprised by how much more reverberant it was than the previous world record holder – it added a whole minute to the record. The tank was constructed to be bomb-proof, leading to a place where a loud low note on a saxophone lasts a couple of minutes before dying away to silence.

What’s your latest project?

I’m just about to start writing a new popular science book called 'Speech Odyssey'.

Where is acoustic research heading?

Much of my research nowadays is focused on audio because of the growth in the number of devices we all carry around with us that use sound, such as mobile phones, and the capability of modern computing to allow the sound to be manipulated. I’m just starting work on a big data project called 'Making Sense of Sound', working with colleagues at Salford and Surrey University. It is looking at how to take the vast amounts of audio data being generated (for example, uploaded online) and trying to develop tools to allow computers to make sense of it.

What is your favorite sound?

The sound of my children playing and chatting away to themselves when they were younger. Now they’re eighteen, and don’t do it anymore!

Professor Trevor Cox BSC, PHD, FIOA (HON)

Location: University of Salford, UK

Position: Professor of Acoustic Engineering, author and freelance radio presenter

Expert: Architectural acoustics, perception and digital signal processing (DSP)

Mission: Improving acoustics, engaging the public

1989: BSc Physics, University of Birmingham

1992: PhD Acoustics, University of Salford

1993: Lecturer, London South Bank University

1995: Lecturer, University of Salford

2006-11: EPSRC Senior Media Fellow

2010-12: President, Institute of Acoustics