In February 2016, the EU launched its Heating and Cooling strategy. The strategy is the first-ever published plan to reduce the enormous amount of energy used to heat and cool buildings throughout Europe. Part of the strategy focuses on minimizing energy waste within industry. That’s because enough heat is leaked into the air and water by industry to meet the EU’s entire heating demand in residential and service sector buildings.

What is district heating?

District heating plants are usually sites where both heat and power are produced at the same time. The heat that is created when producing power is harnessed and used, for example, to heat water within that particular area. This heat would otherwise have been a mere by-product of the energy production. Any energy source can be used in a district heating system, and renewable sources such as biomass, solar energy and waste are becoming more popular, making it an even more environmentally friendly option. But even such district heating plants lose valuable heat.

“Approximately 10–30% of heat can be lost, depending on the network condition and temperatures,” explains Arne Jensen, environmental consultant. “20% of this loss can be related to corrosion, or to loss of water and wet insulation. This is what I focus on helping to save.”

The key to tangible energy savings

Arne Jensen owns a Swedish consultancy company that specializes in finding leaks within district heating systems. Jensen has been using Brüel & Kjær equipment for finding leaks since 1968. He developed his first leak detection equipment using a Brüel & Kjær Integrating Sound Level Meter Type 2225. By adding an accelerometer and headphones, he created an effective system to detect the noise caused by water leakage from pipes, which he patented in Sweden. By listening to the sound at various points within the pipe, he can estimate the size of the leak and its position.

Jensen’s company first uses thermal imaging cameras to find the general area, or hotspot, where the leak has occurred. They then rely on acoustics, vibrations and time measurements to locate the exact location of the leak. Jensen explains, “There is pressurized water in the pipes. When there is a hole in the pipe, the pressure will drop causing vibrations and a hissing noise. This noise is then propagated through the water in the pipe in both directions.”

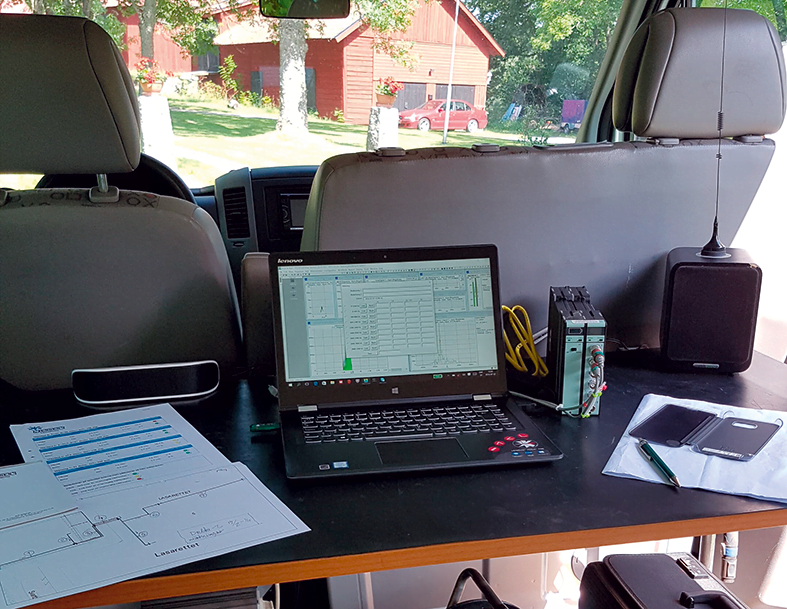

They attach Brüel & Kjær accelerometers to the pipe in different locations and listen with headphones to find two positions on the pipe: one where the noise peaks and one where it begins dropping again. They then use a PULSE data acquisition system to measure the distance between these two positions, or the propagation speed, which then determines the location of the leak – usually within a few metres.”

“A major advantage of PULSE is that it is a Windows®-based real-time analyzer,” explains Jensen. “That means I can make judgements on the probable position of a leak right on the spot. By seeing the data as it is collected, I can decide on the next positions to place the accelerometers and, in this way, I can quickly narrow down the area of the search.”

The solution saves energy and, of course, money. “A typical district heating system in Sweden would serve about 100,000 people and cost EUR 30 million. If 20% of this is lost, it amounts to a loss of 0.6 million EUR per year,” explains Jensen. “District heating might already be a sustainable energy source, but it makes sense to invest in leak detection.”

Detecting leaks before they begin

It is of little surprise that Jensen’s service is popular and that his company is growing. Currently they are developing a permanent monitoring system that detects leaks before they start. “We’ve started monitoring the internal condition of pipes to assess how worn they are. Then they can be repaired before a leak even occurs,” says Jensen. “Last year, one man actually died in Sweden as a result of a damaged pipe that burst. So preventative analysis, or condition assessment, is vital.”

With Jensen’s new monitoring system, there is no leak to create a vibration, so a signal is generated and sent out into the pipes and the response is measured to determine the level of wear on the pipe walls.

“Again, we look for the two positions on the pipe where the noise peaks and begins to drop again, and we measure the propagation speed of the vibration waves. If we know the type of pipe material and its dimensions, then we know what the propagation speed should be if the pipe is healthy. The difference between these two figures tells us if the pipe needs to be changed.”

This type of system monitoring makes it possible to get a complete overview of the maintenance needs of a district heating system, including prioritizing which pipes need to be changed and when, and budgeting for that accordingly. Prototypes of the system are currently being tested in Helsingborg and in Gothenburg, Sweden.

A hole the width of a sewing needle leaks approx. 500 litres/day at a pressure of 2 bars

A hole the width of a sewing needle leaks approx. 500 litres/day at a pressure of 2 bars

Sweden – chilled and sustainable

The EU’s Heating and Cooling strategy commended district heating, specifically using Gothenburg as an example, where 90% of apartment blocks are heated with waste heat from nearby industrial plants and waste incinerators. Until recently, Jensen’s work has primarily focused on colder regions, such as Scandinavia, Russia, the Baltic States, Germany, France and the UK, where heating is crucial and sustain-ability is becoming increasingly valued.

But Jensen is on the front lines of expanding acoustic leak detection across the globe, educating engineers and municipalities, even in warmer regions, about its benefits and application. As the focus on energy and waste prevention intensifies, this technology seems destined to find endless applications around the world.

Abonnieren Sie unseren Newsletter zum Thema Schall und Schwingung