Inspired by his upbringing in the vicinity of the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Cleveland orchestra, sound artist Bill Fontana trained as a composer and has been interested in acoustics and the music that exists within structures since the 70s. Now based in California, his innovative vision has become internationally renowned through critically acclaimed installations on structures such as the Golden Gate Bridge to the Arc de Triomphe and Big Ben.

We wanted to find out a bit more about the man, his work and where he finds creative inspiration.

Finding music in everyday sounds – where did that come from?

Due to my interest in the physics and science of sound, I started to explore how the brain recognizes and organizes patterns of sound in music and I realised that for me, hearing the sounds around me is as beautiful as listening to music, and the idea of creating sonic artworks that intensify the art of listening was immensely appealing. When I moved to New York, I took a class in experimental music composition and got to know John Cage [avant garde composer] who became a great source of inspiration.

In the early 70s, I was hired by the Australian Broadcasting Company to record the sounds of Australia and make sound art projects for radio. At the time, the first FM stereo radio stations were going into operation in Australia, which was an absolute turning point for me as it gave me access to state-of-the-art, mobile sound recording equipment.

Tell us more about how you work?

To explore sound and the environment, you have to consider sound and vibration in three different modes – how it is in the air, in physical material and underwater. Sound moves at different speeds in those three elements, but they are all very reactive to stimuli. The combination of these three listening techniques is very important in explaining the deep musicality of patterns in any situation.

When I develop and research my projects, I use a portable recording studio, containing a set of digital recorders, sound sensors, accelerometers and sometimes hydrophones, to transmit or stream audio from the structure I’m working with to a public site or space, for example, a museum.

How would you define sound sculpture?

The term ‘sound sculpture’ came about in 1968 when I was living in New York. At the time, The Museum of Modern Art had an exhibition called The Machine Show, and it was the first time I’d ever seen any of Marcel Duchamps’ artworks. One of them, called ‘The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even’, was accompanied by a box of notes or conceptual statements. One of these read: “Musical sculpture: sounds lasting and leaving from different places and forming a sounding sculpture that lasts”. When I read that, I thought about all the inspiration I’d derived from John Cage and from my own experiences and decided that from that day forward my works would be defined as sound sculptures.

Do you think everyone can experience sound as music as you do?

People who walk around with headphones listening to music are often turned off by hearing ambient, everyday noise. I think that my brain has developed an ability to recognize patterns in all kinds of sound, so I think that experiencing sound as music is a learned activity where your brain develops an ability to hear this kind of complexity. If I hear new or interesting sounds, I make an imaginary recording in my head, using the same method as I would if I had recording equipment – it’s a self-discipline that keeps my brain focused.

What was the inspiration behind Silent Echoes: Notre Dame?

When I lived in Japan, I became interested in the sonic aspects of Zen Buddhism and meditation. There are some famous temples in Kyoto where Buddhist monks strike large bowl-shaped temple bells that have a very slow decay. The idea is that if you listen and focus all your attention to the point where you lose self-awareness, then the sound becomes you and you get the illusion that the bell doesn’t stop ringing. To explore that metaphor physically, I wanted to see if these magnificent temple bells made sounds when they were not ringing. Attaching accelerometers to the bells revealed that the bells are constantly vibrating, excited by the ambient sound in the Zen garden, so you may think they are silent but by mounting accelerometers you enter a hidden world. To me, this represents the sound of silence – in other words what appears to be an inanimate object, such as the 1000-year-old Buddhist temple bell, is alive and not silent at all.

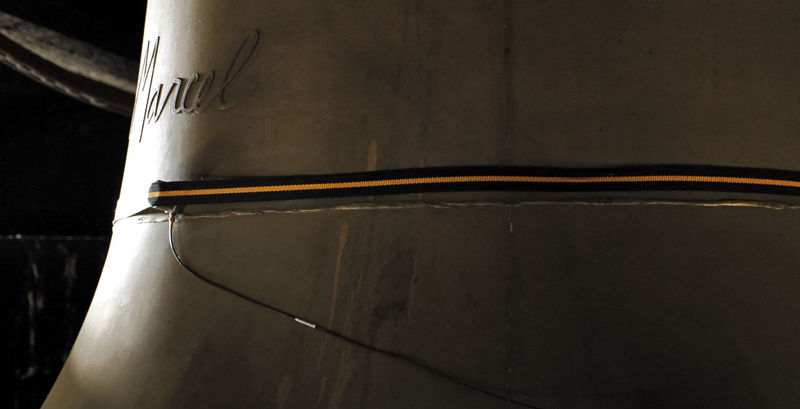

When I found out that the bell towers of Notre Dame had survived the fire and that the bells were undamaged, I knew that accelerometers mounted on the bells would reveal an extraordinary harmonic curtain of resonating echoes as the bells become magical acoustic mirrors, reflecting the surrounding medieval cathedral – made even more beautiful due to the fact that Notre Dame and all its activities have been silenced, but the bells are secretly ringing – living and breathing in the charred remains. Accelerometers allow you to discover the inner life of structures and the ten accelerometers on the bells of Notre Dame are the ‘ears’ listening to the ‘voices’ inside the bells.

With a support network including IRCAM (a French institute dedicated to the research of music and sound and organisationally linked with the Centre Pompidou), l’EPRNDP (Public Institution for the conservation and renovation of Notre-Dame de Paris Cathedral), Hottinger Brüel & Kjær (HBK), the Archdiocese of Paris, the Monseigneur of Notre Dame and the Friends of Notre Dame, and a cultural partnership agreement in place, my project was given the official go ahead. Now with 10 HBK Type 8344 accelerometers (designed and optimized for low frequency and low-level measurements) mounted on the bells, a wireless data network installed, plus some test recordings, I have been able to develop a compositional method for mixing the sound ready for the launch on 8 June.

What happens at the launch?

The premiere of the work will take place at the Centre Pompidou on a beautiful fifth-floor balcony terrace looking south with a direct view of Notre Dame’s bell towers and the urban landscape of Paris. With 30 speakers surrounding the perimeter of the terrace, transforming it into a large listening space, ten channels of live sound coming from the bells will be streamed into a digital mixing system installed by IRCAM.

This work is not a static sound piece. The compositional mix of 10 bells floating and moving through the spatial matrix of speakers becomes a work of beautiful sonic choreography. I hope that the artistic results of these sounds will be as inspiring and breathtaking as I can make them, reflecting the essence of the source material. I want people to look at Notre Dame’s bell towers, hear the sounds and get an amazing and meditative listening experience and realise that the spirit of Notre Dame is alive through its constantly resonating bells.

Sébastien Jouan, head of the acoustics team at Theatre Projects, has contributed to many of sound artist Bill Fontana’s works over the years. Their collaboration, which has evolved into a close and strong relationship, continues with Bill’s most recent sound installation, Silent Echoes: Notre-Dame, with Sébastien acting as project manager. We asked him to tell us a bit more about his involvement with Bill Fontana and this latest project.

How did you get to work with Bill and the Silent Echoes project?

I have worked with Bill for 15 years, helping him with the technical, logistical, administrative and political aspects of various sound installations. Our first collaboration was the Harmonic Bridge project at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London. I was working at Arup’s SoundLab in London at the time, and was responsible for the Harmonic Bridge auralisation, the sound equivalent of visualisation, in 3D ambisonic sound. My part was to recreate the acoustics of the Turbine Hall and add (by convolution) the sounds that Bill had captured with HBK (then Brüel & Kjær) accelerometers installed on the cables of the Millennium Bridge. We successfully demonstrated the work to Sir Nicholas Serota (then Director of the Tate), and Vicente Todoli (the curator at the time), convincing them to commission the installation.

Bill and I kept in touch, working together on Glasgow’s Finnieston Crane in 2013, and later on the concept of a possible installation between the Eiffel Tower and the Palais de Tokyo. Although the plan was never realised, I have indelible memories of our sound experiments on the structure of the Eiffel Tower.

At the time of the terrible fire at Notre Dame in 2019, I had by chance invited Bill to take part in a masterclass for my architecture and music students at the American Art Schools in Fontainebleau, where I teach during the summer. He mentioned the Silent Echoes project and I didn’t hesitate for a second. For me, as someone who also does a bit of sound art in his spare time, working with Bill is like working with the master of the discipline.

What was the involvement of Theatre Projects in the Silent Echoes Project?

I’m Bill’s project manager, representing Theatre Projects. My role involved the installation of HBK accelerometers on the bells (together with Simon Perigot of the Parisian acoustics team), coordinating with IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique), taking care of logistics and administrative aspects to bring the project to a successful conclusion – which we managed, thanks to continuous dialogue on Bill’s behalf with the EPRNDP (in charge of the cathedral’s restoration), the Centre Pompidou, IRCAM, Orange and HBK!

Can you describe the technical configuration and the equipment used?

It is a very simple configuration. On each of the ten bells, we installed an HBK accelerometer, connected to an HBK preamplifier. The outgoing signal is sent to a digital box that supplies the signal to an Orange fibre box that transmits the 10 channels live over the internet. This signal is then received at IRCAM and transmitted to a terrace at the Centre Georges Pompidou, where it is received by a computer and the MAX MSP software that transforms this 10-channel signal into a 30-channel signal, spatialising the 10 bells in a dynamic way.

Why did you use HBK accelerometers and hardware?

HBK accelerometers offer the best vibration response over a wide frequency spectrum. These vibrations are also audible when amplified. They give this very rich sound covering all the resonance frequencies of the 10 bells of Notre Dame where each bell has its own resonance frequency band.

What were the main technical challenges?

The installation of the accelerometers on the bells was a sensitive issue even if wasn’t really a technical one. However, the installation of the fibre by Orange did require a technical discussion. While the cathedral’s clergy were mostly concerned about the accelerometer installation, both issues were discussed with the EPRNDP and the Regional Directorate of Cultural Affairs (DRAC).

What were the highlights of the implementation of Silent Echoes?

Everything. The privilege of accessing the Notre Dame building site, being able to ‘touch’ the great Rose Window with my eyes, collaborating with EPRNDP, IRCAM and the Centre Pompidou. And, of course, working with Bill. We now have a father-son relationship.